The good and the bad of Canada’s drifting economy

Canada’s economy is sputtering. That’s the bad news, and the good news.

Statistics Canada released gross domestic product numbers on Feb. 29 that showed economic activity was up a meagre 0.2 per cent in the fourth quarter, offsetting a meagre 0.1 per cent drop in the previous quarter. For all of 2023, the economy grew by just 1.1 per cent - one of the weakest annual gains on record outside of recessions.

Even worse, most of that annual gain came in the first quarter of the year. Effectively, growth has been flatlined for months and it’s flat across the board.

Just about every segment of the economy is treading water.

So, what’s the good news? It could have been a lot worse.

If your glass is half full, the situation is as good as anyone can expect given the sudden and dramatic increase in interest rates over the past two years. Reminder: The Bank of Canada increased its policy rate by almost five percentage points since March 2022.

Borrowing cost increases of this amount have historically resulted in recessions. The fact that we haven’t had one suggests some resilience.

Some sectors are even doing well, starting with Canada’s exporters who are benefiting from a more robust expansion in the U.S. Export receipts are up almost six per cent on a year-over-year basis.

On the glass half empty side, the topline figures mask deep underlying weaknesses.

Canada’s economic activity is being inflated by surging population numbers. Remove that factor and the economy is shrinking and has been for more than a year.

Even more of a concern is the collapse in business investment. Non-residential business spending fell 6.7 per cent in the second half of 2023 – one of the biggest six-month drops ever. At a time when productivity is faltering, this is very very bad news.

More good/bad

The data provides both good and bad news for Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland, who is in the final stages of preparing her 2024 budget. That the U.S. is doing better than Canada and driving demand for our exports is unequivocally good, though it creates a more challenging narrative for the government, which needs to explain our country’s lagging performance.

More good/bad news for the government: While actual production in volume terms has been flat, prices for the goods we produce are showing signs of re-accelerating. The GDP deflator - a measure of the price of all goods and services produced - increased 3.2 per cent in just the final six months of 2023.

Higher prices are driving gains in nominal incomes. This will help government revenue, while raising some flags around inflation dynamics.

Canadian bank earnings released this week showed a similar picture of a drifting-but-still-afloat economy. Very little growth and falling earnings. But things could have been worse in the face of higher interest rates. Strong earnings from capital markets offset weakness in lending growth and growing provisions for bad loans.

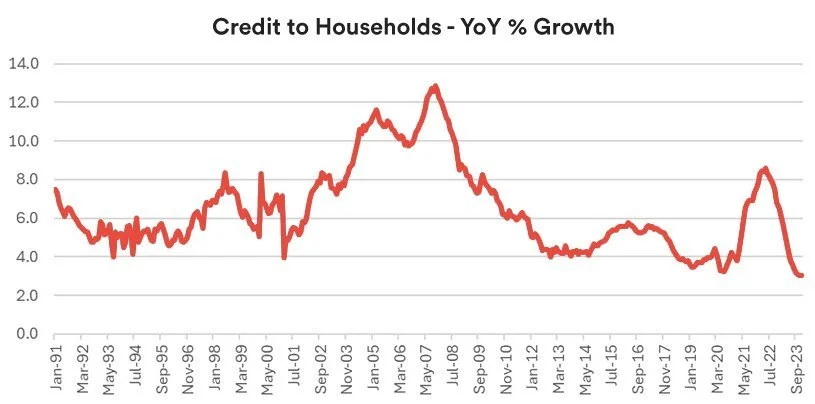

Debt held by Canadian households in December was up just three per cent from a year earlier. That’s the slowest pace of growth since at least 1991.

This is an economy that is in desperate need of some impetus.

The Bank of Canada should start to help in coming months. As long as inflation keeps easing, the central bank will start recalibrating rates. The economy is clearly feeling the impact of higher borrowing costs.

The scope of rate cuts, though, remains the big question.

The Bank of Canada should provide some clues on its thinking at a policy decision on March 6. Officials are likely to tread carefully for three reasons:

The housing market is a complicating factor for the central bank. There still appears to be plenty of pent-up demand for homes that the central bank will be wary of unleashing.

The issue of falling productivity is another concern for the Bank of Canada. It’s inherently inflationary. The more things cost to produce, the more companies will raise prices.

Most important, Bank of Canada officials have worked hard over the past two years to rebuild credibility. They don’t want to move prematurely and make another policy mistake. They’ll want to see inflation pressures continue easing before making any move.