What the new international student cap tells us about housing, growth and Bank of Canada policy

Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Marc Miller speaks to the media during the federal cabinet retreat in Montreal, Monday, Jan. 22, 2024. / THE CANADIAN PRESS/Christinne Muschi

The Canadian government’s decision this week to cap new foreign student permits is an early candidate for the most consequential economic policy decision of 2024.

Immigration Minister Marc Miller announced Monday - from a cabinet retreat in Montreal - that new permits will be capped at about 360,000 annually over the next two years, in order to ease strains on the nation’s housing market. There are also other components meant to reduce demand from international students to study here, as Alex Usher at Higher Education Strategy Associates illustrates in his excellent analysis of the measure.

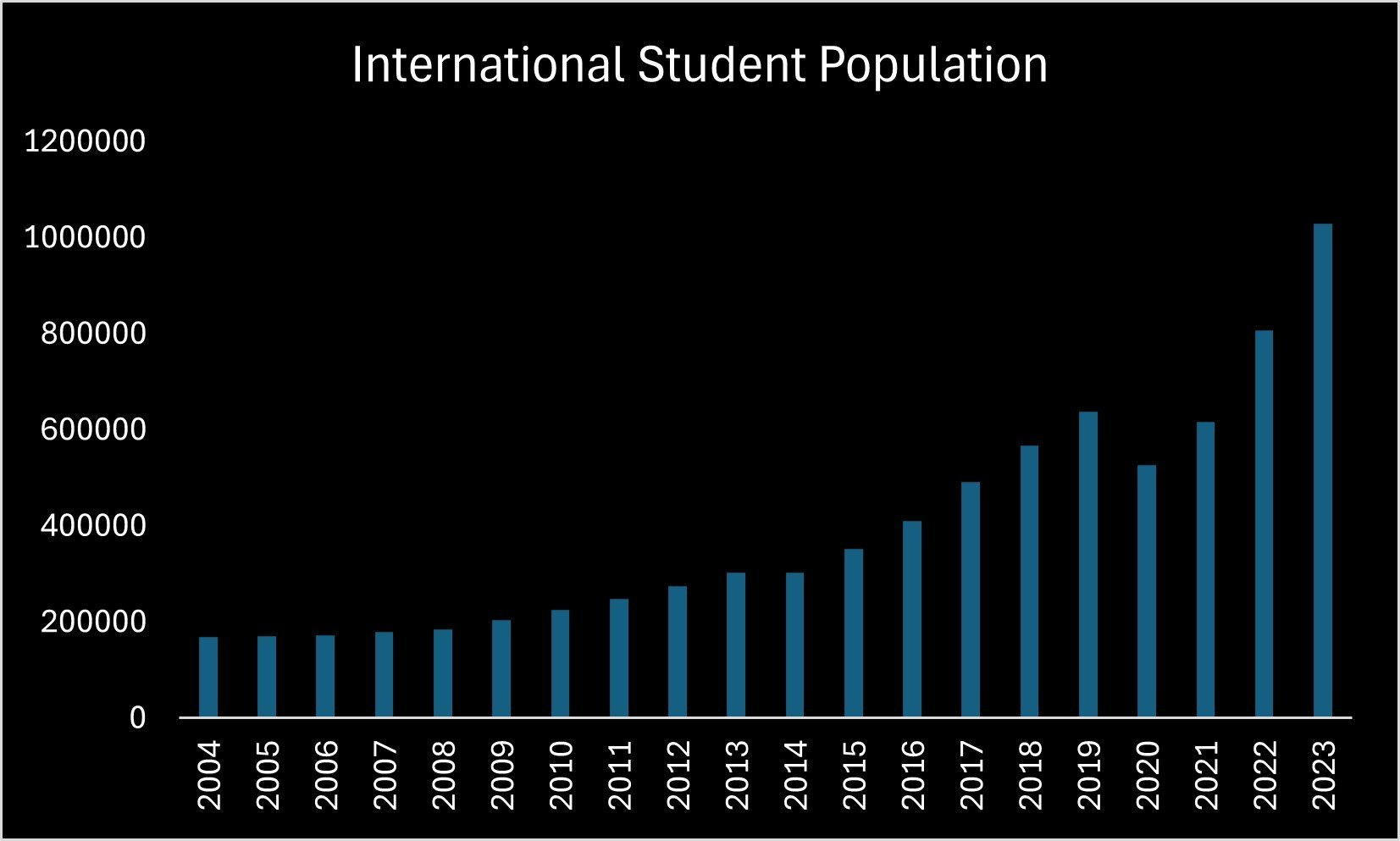

Student numbers had doubled in just three years to over one million, in part because the federal government had been encouraging the influx by making it easier for these students to earn income here. The cap – which doesn’t apply to graduate students - will effectively reduce the number of new permits issued this year by about 200,000, which should at a minimum keep existing international student levels from rising any further.

While the focus for the government is on housing, there will be far-reaching economic consequences with some tough-to-predict outcomes. Pressure on the rental market should ease but that will come at the expense of a weaker growth profile for Canada’s economy and government revenue. The impact on inflation and interest rates is more uncertain but the cap could undermine the Bank of Canada’s ability to deliver on cuts to borrowing costs.

Based on their reaction so far, the move is unequivocally bad for universities and colleges.

The move is also another setback to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s growth model - which has relied heavily on population and government spending to drive economic activity. The past year has seen both of those critical engines running up against severe limits.

Housing

The caps should at very minimum stabilize (if not slightly shrink) the number of people living in the country under the student permit system.

On average, there’s been an annual churn of about 40 per cent among international students over the past eight years, (based on calculations using Immigration Canada data). This means about 400,000 will exit from that status in 2024 through attrition. The caps should ensure the total numbers don’t grow much further beyond the current one million.

Assuming the federal government brings in half a million permanent residents as targeted and keeps levels for other types of temporary migrants stable, population growth should slow to somewhere around 1.3 per cent annually over the next two years. This is within historical averages and a sharp slowdown from the three-per-cent pace we saw for population and the labour force in 2023.

This should take some pressure off housing by bringing population growth more within reach of new supply. But it will only limit further shortages and won’t solve the housing crisis, which hinges more on our ability to ramp up construction. The likelihood is that strains on housing will persist for years, and moves to constrain international migration will likely become permanent features of the system rather than a temporary move.

The Bank of Canada, in its quarterly policy report released on Jan. 24, published a revealing chart that shows the connection between population growth and rent inflation.

Rent inflation has been hovering at near eight per cent – a four-decade high - even as broader price pressures have come down.

Growth

The material slowdown in population growth will pose a major test to Canada’s medium-term outlook. It’s less certain now, for example, the economy can return (from little growth in 2024) sustainably back to two per cent growth within the next year, as economists and the government currently project.

Growth is fundamentally a function of two things: increasing the number of workers and making them more productive. Unfortunately, our labour productivity has been falling, which means we rely increasingly on only population growth through immigration to drive growth.

The less our labour force grows, the less potential our economy has to expand.

This slowdown in supply of new workers, meanwhile, will only be aggravated by aging demographics that are already putting downward pressure on labour force participation.

Weakening potential growth has important implications on everything from the federal government’s fiscal projections to Bank of Canada policy. The federal government’s fiscal plan is based on working-age population growth of about 1.6 per cent on average between 2023 and 2028, as the table below shows.

The Bank of Canada is also predicting faster population and underlying economic growth than we’re likely to get thanks to the cap on international students.

Inflation and interest rates

One would imagine that Miller’s announcement early Monday morning (before 9 a.m.) would have come to the immediate attention of the Bank of Canada’s governing council, which was meeting at the central bank’s headquarters in downtown Ottawa to deliberate on its Jan. 24 policy decision.

The cap was new and material information that came too late to be seriously incorporated into their analysis. There’s no mention of it in the policy statement, the opening remarks by Governor Tiff Macklem at his press conference or in the quarterly projection report that was also released on Wednesday.

When asked about the cap at the press conference, Senior Deputy Governor Carolyn Rogers cited the potential for less pressure on housing but had nothing to say about the underlying impact of slowing population on economic growth.

The truth is, the impact on inflation and interest rates is not clear cut.

At its policy decision this week, the Bank’s governing council decided to hold its policy rate unchanged but indicated strongly that they are poised to cut interest rates as long as inflation pressures continue to abate.

And they believe inflation will continue to abate because the economy is entering a period of economic slack that will cool demand.

The intuitive argument is that less international migration means less demand, which should continue to cool the economy. For example, Desjardins warned in a recent report that curbing the population of non-permanent residents could deepen the economic downturn this year.

This should give the Bank of Canada more scope to cut rates. But there’s a hiccup to this story.

Student caps will also be limiting the influx of new workers into an economy that is actually struggling to absorb them because of slowing growth and higher interest rates. We’ve already seen a relatively significant increase in the unemployment rate that is disproportionately impacting new entrants to the labour force.

So, fewer available new workers will minimize slack in the economy and keep the labour market tighter than it would have been otherwise.

This will severely test the Bank of Canada’s rate cut hypothesis.

The central bank expects inflation to abate because it believes population will continue growing at elevated levels into a weakening economy, creating excess supply that will allow for rate cuts.

What’s the central bank’s projection for population growth? As this clip from the Bank of Canada’s monetary policy report shows, it’s “just below” two per cent annually, which may no longer be a reasonable assumption.

A markdown of that population assumption (and with it, potential growth) could have implications on its analysis around interest rates and inflation.